For Ezra, the prison bureaucracy and the restrictions on inmates, along with the repressive legal environment in Allegheny County, were insurmountable barriers to justice.

Wrongfully Convicted Almost Fifty Years Ago and Still in a Pennsylvania Prison

by Amy Knight

If Ezra Bozeman were to be exonerated today, he would hold the U.S. record for the innocent person who served the most time behind bars, according to the National Registry of Exonerations which tracks time served for wrongful convictions.

As a specialist in Russian politics, I have written widely about the repressive legal system in Russia, where individual rights are routinely abused by Vladimir Putin’s autocratic regime. But the case of Ezra Bozeman, a 68-year-old Black inmate at the state correctional institution in Chester, Pennsylvania, has reminded me of the shocking abuses that persist in our own system of justice.

Bozeman, whom I visited this spring at Chester SCI, is a highly intelligent, articulate, and kindly man, respected by the staff and other inmates. He has been incarcerated since May 1975, when at age nineteen he was arrested in Pittsburgh for a murder and robbery that had occurred there four months earlier, on January 3. The victim was Morris Weitz, co-proprietor of Highland Cleaners, who was shot as he stood behind the cash register. Contrary to Bozeman’s constitutional rights, he was not brought before a magistrate for arraignment or informed of the evidence and charges against him. And he did not see a copy of the criminal complaint until three years had passed. No wonder. The complaint was found unissued, without the required probable cause affidavits and falsely stating that he had been arrested “on view,” meaning that the arresting officer had witnessed him committing the crime. None of the investigating officers testified and so were not required to address the missing affidavits of probable cause made by the alleged witnesses and how the officer could claim the arrest that took place four months after the crime was “on view”.

Convicted by an all-white jury of second-degree murder and robbery in October 1975, Bozeman, has been adamant about his innocence and that he was nowhere near the scene of the crime. He was sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. The only eyewitness against him, Thomas Durrett, had been detained briefly in January as a suspect in the Weitz murder and in April was arrested and charged with the crime. But the evidence against Durrett was weak, and prosecutors needed a conviction for the crime. So in early May they arranged Durrett’s release on only $5000 bail, and, although he never mentioned Bozeman to investigators during his twelve days in custody, Durrett then claimed that he saw Bozeman commit the murder and asked his two close friends to go to the police and say that they heard Bozeman admit to the crime. Several months later, just as Bozeman’s trial began, prosecutors convinced the judge to dismiss the charges against Durrett.

The trial was a stark example of judicial malfeasance. At the prosecution’s behest, the judge, Albert Fiok, refused to allow discussion before the jury of Mr. Durrett’s release on bail—clearly because it would make Durrett a less credible witness. Mr. Bozeman’s trial attorney, John Pope, in his own testimony at Mr. Bozeman’s appeal, describes himself as a “personal friend” of the prosecutor, Jeffrey Manning. Mr. Pope filed no pre-trial motions and neglected to request discovery or call defense witnesses. He failed to challenge the glaring inconsistencies in the testimonies of Durrett and his friends and did not object when Judge Fiok falsely told the jury before deliberation that Mr. Bozeman had actually confessed to the crime (not that the friends of Durrett claimed he had confessed).

Bozeman, who studied law in prison, would cite these violations of his legal rights in the numerous petitions for post-conviction relief and habeas corpus that he filed over the years. But all were denied, usually because they did not meet the “timeliness” criteria.

Then, in 2017, Thomas Durrett recanted key elements of his testimony in an interview with the Pennsylvania Innocence Project. Durrett denied that Mr. Bozeman told him he planned to rob the cleaners and said he never saw Bozeman with a gun. Durrett also insisted that neither he nor his friends ever heard Bozeman say he had killed Weitz. But Mr. Bozeman’s subsequent petition for post-conviction relief was unsuccessful: the court concluded in 2019 that the verdict against him “did not rest solely on the testimony of Durrett.” Never mind that the only other evidence against Bozeman came from Durrett’s close friends, who were recruited by Durrett to testify.

According to a 2022 report by the National Registry of Exonerations, misconduct by law enforcement officers and prosecutors led to wrongful convictions in 78 percent of the 638 murder exonerations of Black defendants since 1989. The most common types of such misconduct were concealing exculpatory evidence and witness tampering. Mr. Bozeman, as well as the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, are convinced that access to the homicide files in Bozeman’s case would contain other important evidence that would prove Bozeman’s innocence, even showing that prosecutors made a secret deal with Mr. Durrett. But my request to the Allegheny County District Attorney’s Office for copies of those files was denied, despite the fact that the case has been closed for decades. Apparently, no one there wants to open a pandora’s box, even if it condemns Mr. Bozeman, incarcerated for almost fifty years, since he was 19 years old and now badly crippled from untreated nerve damage to his spine, to spend the remaining years of his life behind bars.

Is sentencing a nineteen-year-old to life imprisonment by gravely violating his legal rights any different than shipping a young Russian off to the GULAG with no requirement for formal charges, no independent legal representation, and no access to the evidence against him?

Ezra Bozeman’s Story In His Own Words

On January 3, 1975, Morris Weitz was fatally shot inside a Pittsburgh dry cleaners.

I am innocent because I wasn’t there. I didn’t own a gun. I didn’t do it! There was no evidence and no witnesses for four months and then the prosecutor arrested Tommy Durrett, my then girlfriend’s brother. I didn’t have an alibi because I was detained four months after it happened and there was nothing that stood out for me about that day.

At the time of the murder on January 3, 1975, I had been in Pittsburgh for three months and was living with a young woman, Bonnie Durrett.

Tommy Durrett, Bonnie’s brother, was questioned by the police in early January. I heard Tommy Durrett say he told the police that he was at, a supermarket near the shooting, and he didn’t know anything about the murder, and he was released from police custody. He was questioned again in March, reaffirming his account, again with no mention of me.

Approximately three months later, April 21, 1975, Durrett was arrested and charged with murder/robbery for this case and held in the Allegheny County Jail. Following a Coroner’s Inquest on May 1, 1975, Durrett was held for Court on the murder\robbery charges. After over a week in jail, Durrett suddenly remembers that he had been in the pizza parlor next to the cleaners when the crime occurred and he witnessed me shooting the victim. Affidavits of these accusations have never been provided.

On May 1, 1975, I went to Tommy Durrett’s mother’s house with his sister while she checked on events at Tommy’s hearing. The police entered the house without a warrant and took me into custody. No Arrest Warrant / Criminal Complaint or Affidavit of Probable Cause were served. For the subsequent nine days I was held with no idea what the charge was.

My first court appearance was the Coroner’s Inquest on May 9, 1975. I was represented by Public Defender, Stephen Swem. No Criminal Complaint had been issued and Mr. Swem did not request a copy of the Criminal Complaint or Affidavit of Probable Cause from the Coroner prior to the start of the Inquest. I was bound over to stand trial for murder/robbery without these basic documents being processed and issued.

The Inquest proceeded without counsel objecting to me not being charged or receiving notice of the charges and accusations and without filing a writ of habeas corpus at this pretrial stage which would have either had me released at that point or provided the documents and rulings on which to base my appeals.

As for Tommy Durrett, the ‘”eye-witness” whose testimony was the only evidence of my involvement, after making the “unheard of” low bail of $5,000, proceeded to gather two of his close friends, Gregory Clark and Gaylord Veney, taking them to his attorney, who then took them to the District Attorney, and the three friends made a circumstantial case against me, with his friends claiming to overhear me admit my involvement and alleging that I had threatened each of them to keep silent. Durrett, and Veney had both been questioned by the Police in January 1975, and had reported to the police in writing or orally that they were not involved and didn’t know anything about the crime.

On May 2nd, 1975Assistant DA, Howard Hilner, supported a petition filed by Durrett’s lawyer for Durrett to have a $5,000 which was so unusual the Judge hand wrote on the bail petition “The above bond recommended by and consented to by Asst. DA, Howard Hilner”.

The evidence is clear that the prosecutor’s case against Durrett was weak, so the prosecutor coerced and bargained with Durrett to testify against me to save himself from being charged with the murder. The charges against him were maintained for five months, just being dismissed hours before testifying against me He also falsely claimed he was getting nothing for his testimony even though in addition to the murder/robbery charges being dropped, a pending Marijuana Sale and Distribution charge was also later dropped.

An examination of the documented events substantiates the outright collusion that occurred, including the judge refusing to inform the jury of the unusual bond arrangement for Durrett recommended by the DA as well as his dropping the charges against Durrett the day before Durrett’s testimony against me.

My attorney, John Pope, who later identifies himself as a “personal friend” of the District Attorney, never saw the Complaint so that he and I and the judge could see that in fact it was never processed, Discovery never requested, a Pre-Trial Motion never filed. Pope never made any objections that would allow me to know the nature and cause of the accusations against me or the opportunity to prepare a defense or make appeals on these critical issues. As a 19-year-old kid without a high school diploma I had no idea of the devastating door my lawyer was closing that would bar the grounds for my appeal.

In order to maintain the validity of these false testimonies, the District Attorney kept the homicide investigators off the stand and away from cross examination, and concealed every police report, and investigators’ notes and statements in the whole case.

In 2019, Tommy Durrett recanted his testimony to a Pennsylvania Innocence Project Investigator See investigator’s internal report two days following his interview. This recantation was judged in an appeal to be invalid because of other substantiating evidence (the fact that the only other testimony was that of Durrett’s best friends which Durrett also told the IP investigator was not accurate was deemed irrelevant).

I have been fighting for 48 years for access to the police investigative reports, the “H files that have been withheld by the Allegheny County for all this time even though I know they would provide the new evidence I need to get back into Court if not prove my innocence immediately.

Sole Witness Recantation to PA Innocence Project Investigator

TO: FILE

FROM: ZACH STERN, STAFF INVESTIGATOR

SUBJECT: THOMAS DURRETT

CONTACT: 7500 UPLAND ST, PITTSBURGH, PA

CASE: EZRA BOZEMAN

REPORT DATE: 2017-05-03

On Monday, May 1, 2017, at approximately 05:00pm, I interviewed Thomas Durrett at his home located at 7500 Upland St in Pittsburgh, PA. I introduced myself, handed Mr. Durrett a business card, and explained the reason for the visit.

Mr. Durrett essentially told me on the day of the murder, he and Bozeman drove up to a pizza store. Bozeman went across the street to Highland Cleaners, and when Bozeman walked in, many others walked into the Cleaners at that time, too. Durrett then heard a couple of gunshots and saw multiple people run out. Mr. Durrett saw Mr. Bozeman run out in the crowd of people, and did not know if he was holding anything, let alone a gun. Durrett did not witness the shooting; he only heard the gunshots and saw multiple people run out. Durrett denied Bozeman telling him he planned on robbing the Cleaners while they were in the car on the way there, as he testified to at trial.

Mr. Durrett also told me he and Mr. Bozeman never had a conversation regarding this shooting. Bozeman never confessed to him, or threatened him that “if anyone says anything, they’ll be taken care of.” I asked him if Gregory Clarke or Gaylord Veney could have ever heard a conversation like that, and again, Durrett denied the possibility.

Durrett claims he was charged with the murder, and the police were threatening to put him away for life unless he implicated someone else in the murder. So, he told police he saw Bozeman commit the murder. Durrett could not explain why he chose to implicate Bozeman in this crime.

Towards the end of the conversation, Durrett said Bozeman does not deserve to get out of prison and that he’s not a good person. At that point, he told me to get off his property and he did not want to talk about all of this anymore. At that point, the interview was concluded and I left.

Nothing further.

Preliminary Arraignment and Complaint Documents

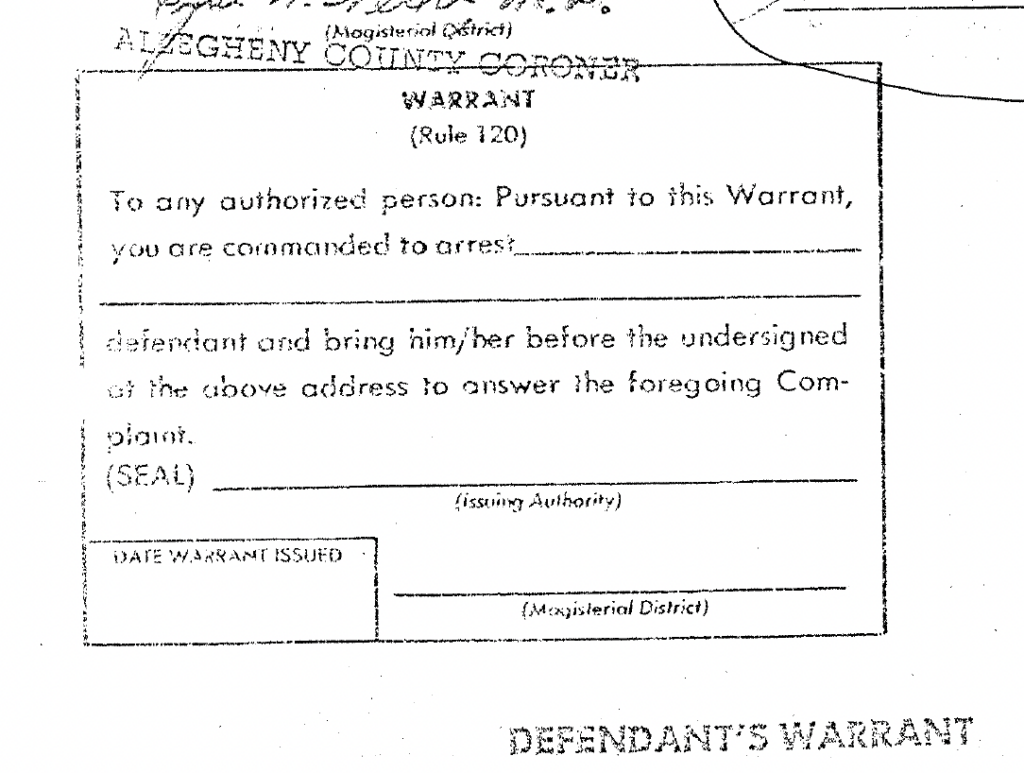

On page 1 of this document (Complaint for Murder), the Warrant box is empty (bottom left corner) and also on page 3 (Complaint for Armed Robbery).

Where it reads “See Supplement” there was no supplement. This copy, the Defendant’s Copy, was found three years later still attached in the Clerk of Court’s file. Thus, Ezra never knew that he was detained without due process because his lawyer never requested to see these Constitutionally required documents to establish that there was probable cause for an arrest to be made.